The problem

If you're a runner, you know the daily struggle: when should I run, and what should I wear? Most weather apps just show you numbers (temperature, humidity, wind speed) but they don't actually help you make a decision. I found myself doing mental math every morning, weighing all these variables in my head. Sometimes I'd get it wrong and end up overdressed, freezing, or caught in unexpected rain.

How I built the solution

WeatherToRun started as a simple idea: what if the app could do that mental math for me? Instead of showing raw weather data and leaving interpretation to the user, it analyzes conditions and gives you a straight answer: is it a good time to run or not?

The core of the app is a scoring system that combines multiple weather factors into a simple 1-100 score. A color-coded "Bad," "OK," or "Good" rating makes the decision even faster. No more guessing.

Here's what I built:

- A scoring algorithm grounded in research: I spent time reading about how weather actually affects running performance. The weights aren't arbitrary: temperature gets 30% because the optimal range (44-59°F) comes from marathon performance studies. Wind gets 25% because a 10mph headwind can slow your pace by 8-15 seconds per mile. Dew point (20%) turned out to be more reliable than humidity for predicting comfort. These details matter.

- Edge-first for speed: The API routes run on Vercel's Edge Runtime, which means ~50ms cold starts instead of the ~5000ms you'd get with traditional serverless. For a utility app you check for 10 seconds, this makes a huge difference.

- Smart caching everywhere: Weather data doesn't change every second, so I built a multi-layer caching strategy: hourly cache at the edge, 1-hour stale time on the client with TanStack Query, and coordinate rounding to 4 decimal places so nearby users share cache hits.

- Personalized clothing recommendations: Everyone runs hot or cold differently. A simple "More layers" / "Less layers" toggle lets you customize the gear suggestions.

- Offline-ready PWA: The app works without a connection and can be installed on your phone. More on the caching strategy below.

The goal was to make something genuinely useful, something I'd actually reach for before heading out the door.

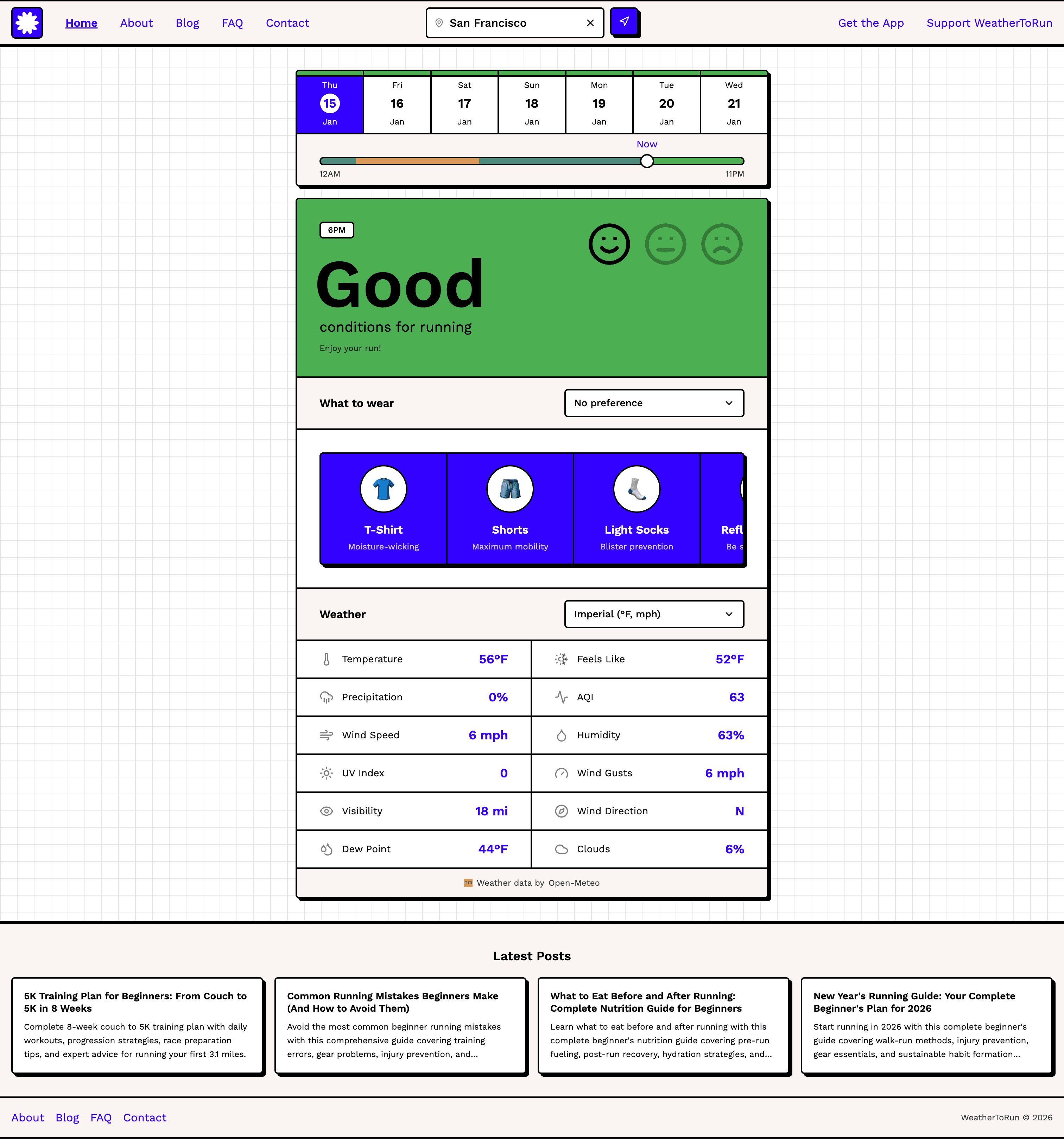

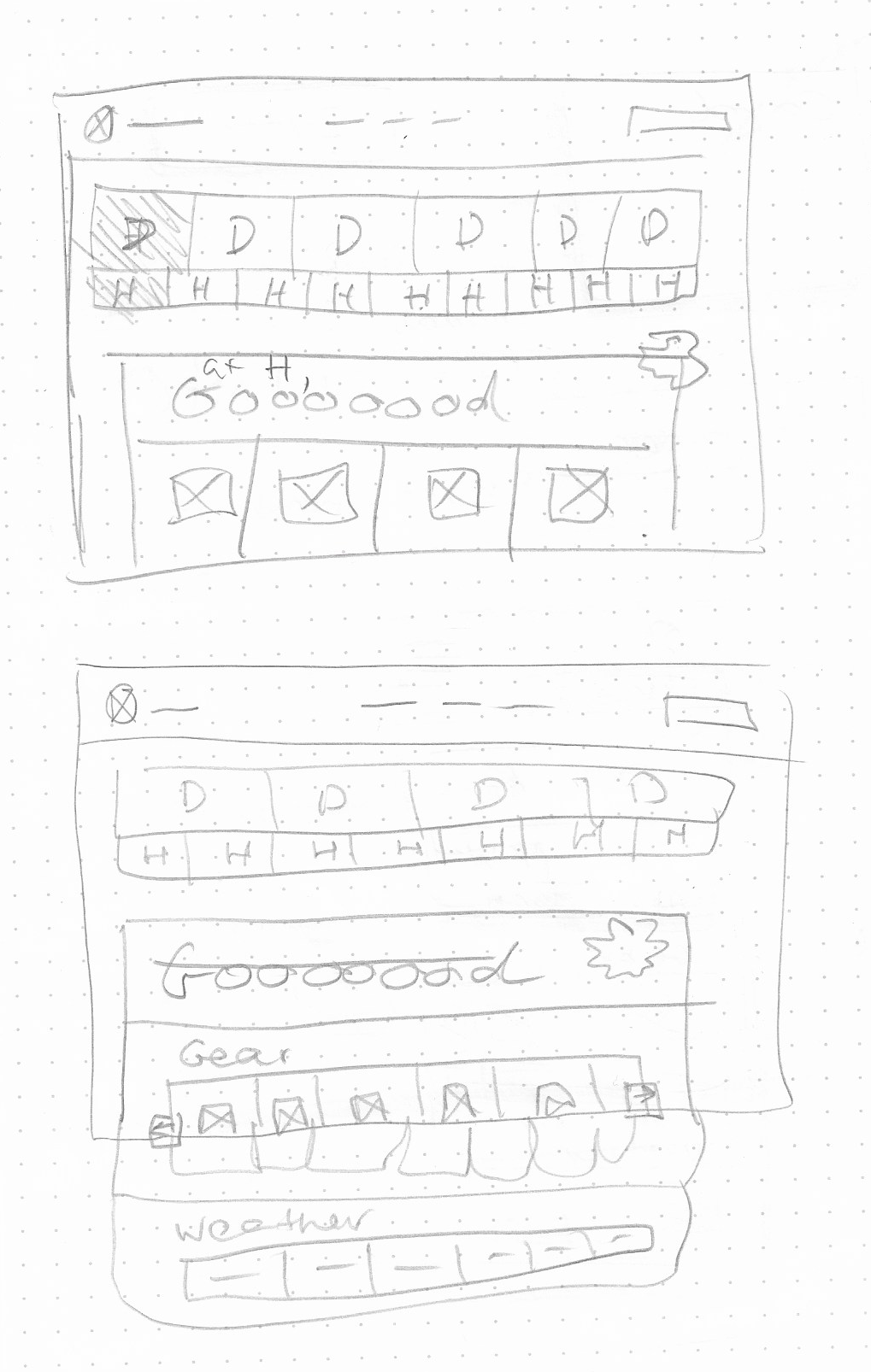

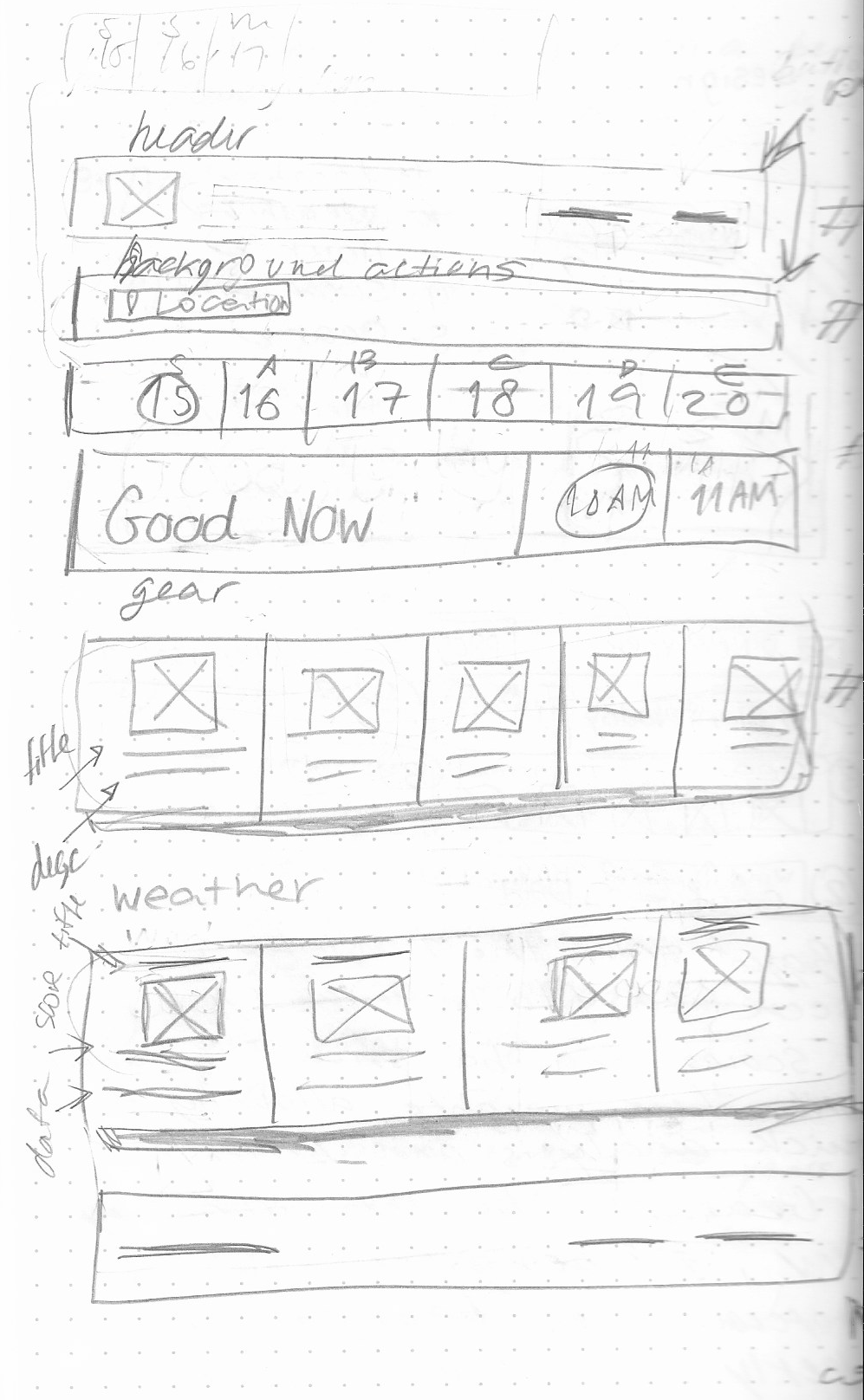

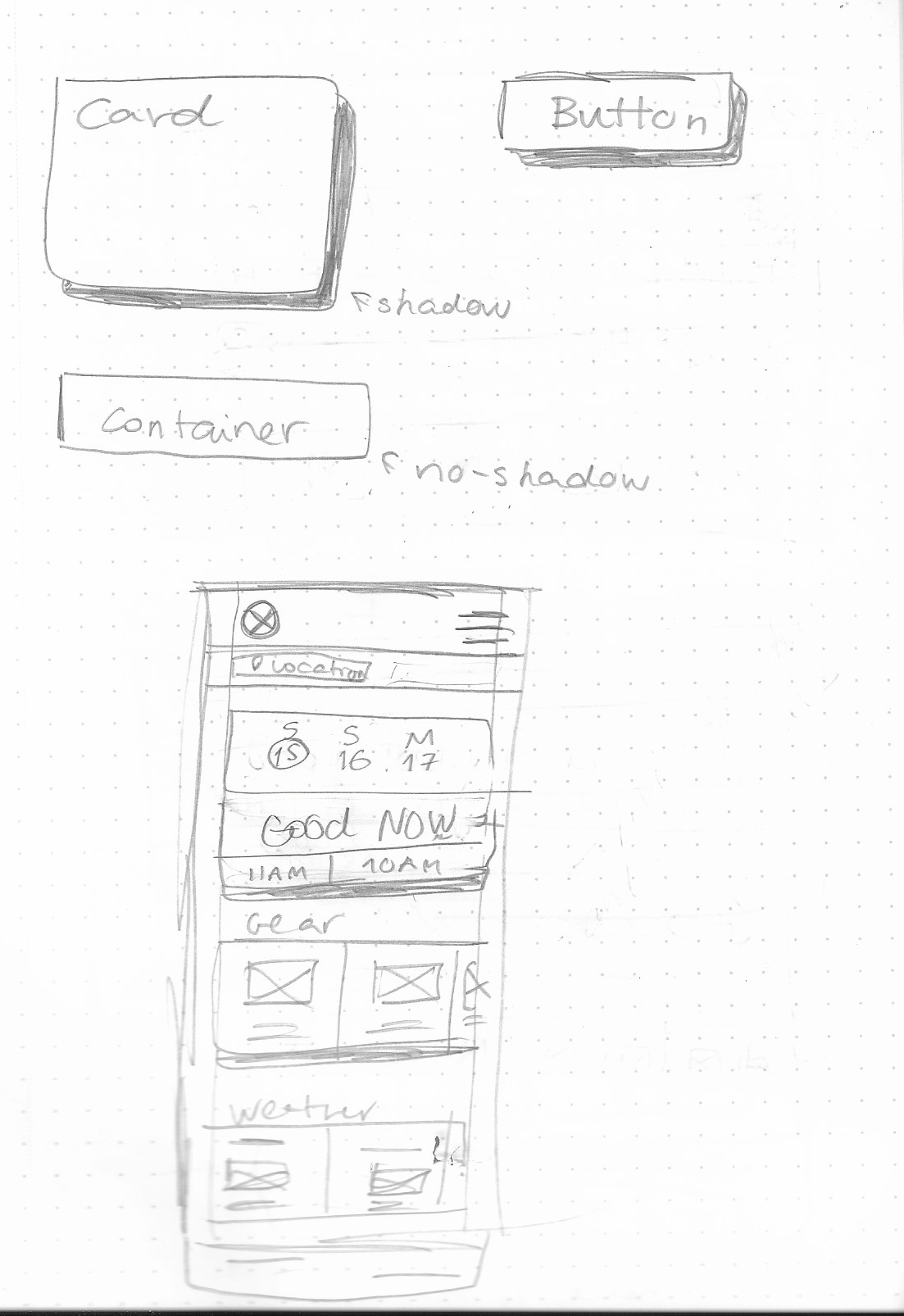

From sketch to UI

Before writing any code, I grabbed a pen and sketched out how the app should feel. What's the first thing a runner needs to see? The score and what to wear. Everything else is secondary. These rough wireframes helped me nail the hierarchy before getting lost in implementation details.

Initial wireframes exploring the main view, component structure, and user flow design.

Making it work offline

I wanted WeatherToRun to feel like a native app: installable, fast, and functional even with spotty connectivity. But PWA caching isn't as simple as "cache everything." I learned this the hard way.

Different assets need different strategies. I used Workbox to set up:

- CacheFirst for static stuff (scripts, styles, images) with a 30-day expiration. These rarely change, so hitting the cache first saves bandwidth.

- NetworkFirst for the manifest with a 3-second timeout. Users get updates when online, but there's always a fallback.

- NetworkOnly for navigation and React Server Component payloads. This one surprised me. I initially cached these, but ran into sync issues where stale RSC data caused weird UI states across devices. Sometimes the right caching strategy is no caching at all.

When you're offline, you see a friendly offline page instead of a browser error. It's a small touch, but it makes the app feel more polished.

The app can be installed on your home screen and runs in full-screen mode. It feels native, even though it's just a web app.

Handling the real world

Weather apps need to be fast. If someone has to wait, they'll just look out the window. But more importantly, they need to be reliable. External APIs go down. Rate limits kick in. Networks are flaky. I spent a lot of time making sure the app handles all of this gracefully.

When things go wrong

The app doesn't just hope the weather API responds. It plans for failure:

- Retry with backoff: If I hit a rate limit (429) or a network blip, the app automatically retries with increasing delays, capped at 10 seconds. This handles temporary issues without hammering the API.

- Timeouts that make sense: The weather API gets 8 seconds. Air quality data (displayed separately, not part of the score) gets 3 seconds. If AQI fails, the app keeps working with just weather data. Graceful degradation over complete failure.

The scoring math

I mentioned the scoring algorithm earlier, but here's the full breakdown:

| Factor | Weight | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 30% | 44-59°F is the sweet spot for performance |

| Wind | 25% | A 10mph headwind costs you 8-15s/mile |

| Dew point | 20% | Better than humidity for predicting discomfort |

| Precipitation | 15% | Rain, snow, storms |

| UV index | 10% | Sun exposure adds heat stress |

The algorithm also handles 30+ weather codes from thunderstorms to freezing rain, each with appropriate score penalties. And because weather apps often report misleading wind data, I blend gusts with sustained speed (70/30 weighting) for more accurate real-world scoring.

Finding the app

For discoverability, I added JSON-LD structured data across all page types (FAQ, Blog, Weather pages), dynamic Open Graph images for social sharing, and proper sitemap/robots.txt configuration. The technical SEO stuff that helps people find the app in the first place.

Knowing when things break

I integrated Sentry for error monitoring. When something fails in production, I get context (what operation failed, which coordinates, what the API returned) without exposing any user data. This has been invaluable for catching edge cases I never would have found in local testing.

Keeping weather data fresh

I ran into an interesting problem with caching. Initially, I used Next.js's time-based ISR with a 2-hour revalidation window. Sounds reasonable, right? The issue is that ISR only triggers revalidation when someone visits after the stale period expires. For a page that doesn't get much traffic, a visitor might show up 12 hours after the last cache update and see 12-hour-old weather data on their first load.

That's not great for a weather app.

The fix was to stop waiting for visitors to trigger revalidation and instead proactively invalidate the cache on a schedule. I set up a cron job that hits a secure /api/revalidate endpoint every 30 minutes, regardless of traffic.

Here's what made this work:

- Cache tags: I added

next: { tags: ['weather'] }to the weather API fetch calls. This lets me invalidate all weather-related data at once usingrevalidateTag('weather')instead of manually tracking every cached page. - Stale-while-revalidate: Next.js 16 introduced

revalidateTag(tag, 'max')which serves the cached content immediately while fetching fresh data in the background. Users never wait for the fetch. They always get an instant response. - GitHub Actions as free cron: Vercel's Hobby plan limits cron jobs, but GitHub Actions gives you 2,000 minutes per month for free. A simple workflow that runs every 30 minutes and hits the revalidation endpoint was all I needed.

- Graceful degradation: If the cron ever fails, the 1-hour fallback

revalidateon the page still kicks in when traffic arrives.

The endpoint itself is protected by a secret token stored in environment variables. Without the right REVALIDATE_SECRET, the endpoint returns a 401.

Now users always see weather data that's at most 30 minutes old, whether they're the first visitor of the day or the hundredth. Low-traffic pages stay just as fresh as high-traffic ones. It's a simple solution that works well.

What I learned

Building WeatherToRun changed how I think about building apps. A few things stuck with me:

Less data, more synthesis. The value wasn't in showing more information. It was in processing it intelligently. The scoring algorithm took real research and thought, but it's what makes the app actually useful instead of just another weather dashboard.

Reliability is invisible until it's not. Users don't notice retry logic or timeout handling. They just notice when an app "works" or "doesn't work." The investment in graceful degradation pays off every time an API hiccups and the app keeps running.

Caching is harder than it looks. The multi-layer strategy (edge, client, coordinate rounding) wasn't obvious from day one. It evolved from understanding access patterns: weather data is stable for hours, and neighbors can share cache hits. But caching RSC payloads broke things in subtle ways. Sometimes the right answer is to not cache.

Edge changes everything. Moving to Edge Runtime dropped cold starts from 5 seconds to 50 milliseconds. For a quick-check utility app, this is the difference between feeling instant and feeling sluggish.

Small personalization goes a long way. Just adding a "More layers" / "Less layers" toggle made the clothing recommendations feel personal. Not everyone needs a settings page with 50 options. Sometimes one toggle is enough.